Life Cycle Management in Engineering

One of the benefits of working at a larger company is that you’re able to access and benefit from the wealth of knowledge that senior engineers from all sorts of backgrounds bring.

This post comes off the back of a professional development session that a colleague of mine put together to share knowledge on life cycle management and its applications in systems engineering. What that means, why it’s relevant, and how we can use it (or already do) as engineers.

This post will reference some of the concepts I touched on in my previous post about systems engineering — particularly ideas around requirements, integration, and verification — so if any of those feel unfamiliar, it might be worth starting there!

Why Talk About Life Cycle Management at All?

Despite the word 'management' making it sound less technical and further from what most engineers may normally spend time on, the concept is actually something that all engineers are a part of regardless of their work.

Almost everything we design as engineers goes through stages:

- Someone has an idea or identifies a need

- Requirements are defined

- Something gets designed and built

- It’s tested, integrated, and used

- It’s maintained, upgraded, or adapted

- And eventually, it’s retired, disposed of, or recycled.

Life cycle management is simply the discipline of acknowledging those stages upfront, and deliberately managing engineering decisions with the entire lifespan of the system in mind — not just the exciting design phases at the start.

Phones, trains, aircraft, spacecraft, software platforms — none of them exist in a vacuum. They live long, messy lives in the real world. And life cycle management is important because it puts those lives into context from the beginning.

So… What Is a Life Cycle?

At its simplest:

A life cycle is the full set of stages a system passes through from concept to retirement.

That includes not just building the thing, but:

- Defining what it needs to do

- Operating it in the real world

- Maintaining it as things wear out or change

- Supporting the people who use it

- And eventually disposing of it, safely and responsibly

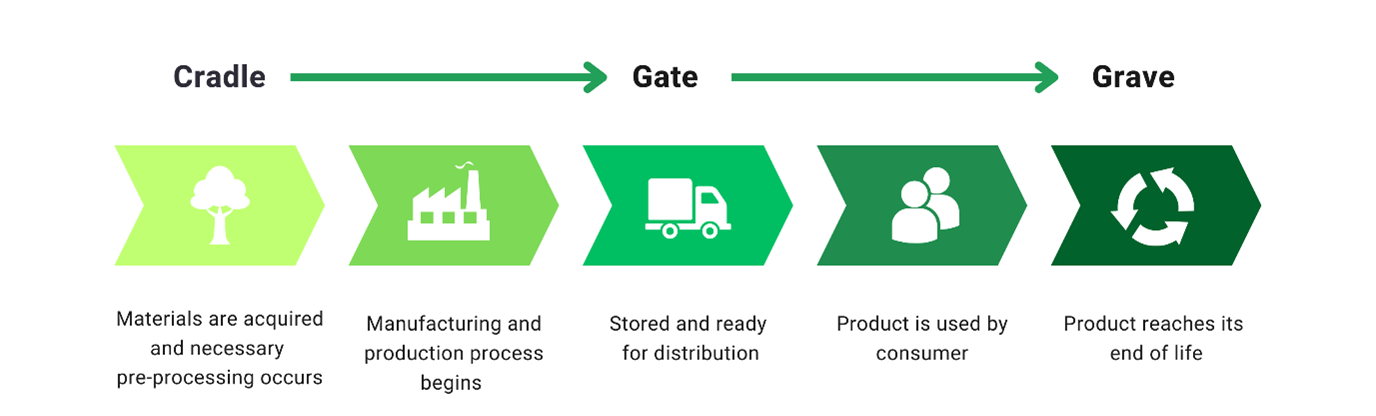

Earlier interpretations of life cycles focused on a fairly linear view — often described as “cradle to grave”. You design something, build it, use it, and eventually scrap it.

More modern interpretations expand on this:

- "Lust to Dust" covers inception to full retirement, considering everything from the earliest idea through to decommissioning.

- "Cradle to cradle" introduces sustainability — where end-of-life components are recycled or reused to form new systems.

These distinctions matter, especially in industries like rail and aerospace, where systems can be in service for decades, and decisions made early on can have long-lasting consequences.

An Example of Life Cycle Thinking Through an Engineering Lens

One example from the session took an F1 car, and gave an idea of what its full life cycle might look like, piece by piece.

Here's the rundown:

Before anything gets built, engineers define what’s required to get the car running: performance targets, safety constraints, regulations, interfaces between subsystems (what needs to communicate with what).

From there, those subsystems are designed and tested individually - the suspension for example.

Once confidence is built at that level, those subsystems are integrated together — engine with electronics, electronics with control systems, control systems with the chassis.

Testing doesn’t stop once the car “works”. It evolves as the system grows and the team is satisfied the car operates to achieve all the requirements set at the beginning - OR, any new ones that get defined as the project goes on.

Then comes operation: racing, monitoring performance, identifying failures.

Maintenance becomes a core activity — components wear out, performance degrades, upgrades are introduced.

And eventually, parts are retired, reused, or redesigned.

This same pattern appears everywhere — from spacecraft propulsion systems to railway signalling infrastructure. The scale changes, but the structure of the life cycle doesn’t.

Different Life Cycles for Different Problems

One of the most important takeaways I got from the session was that there isn’t a single “correct” life cycle model.

Different projects demand different approaches.

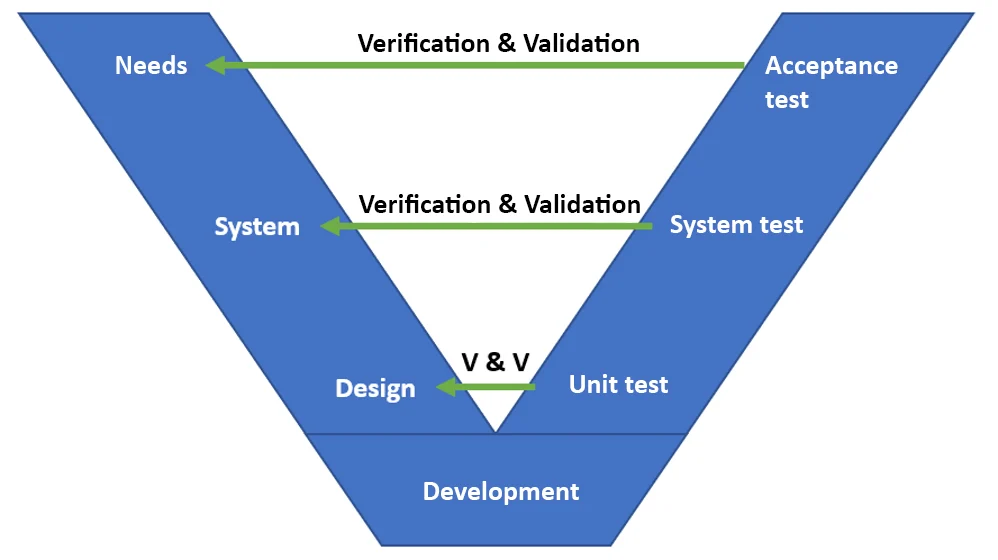

The V-Model

This is one of the most well-known life cycle models in systems engineering, particularly for large, safety-critical projects, and I touched on it in my previous post.

On the left side, you define and decompose requirements — from high-level system needs down to detailed designs.

On the right side, you build back up through testing — verifying and validating each level against what was defined earlier.

It works best when:

- Requirements are well understood early

- Change is expected to be minimal

- Assurance and traceability are critical

This is common in industries like rail, defence, and aerospace.

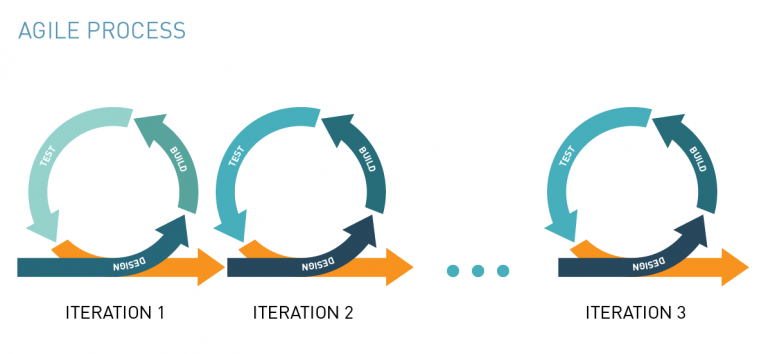

Iterative Life Cycles

Sometimes, you don’t fully know what you need at the start.

In those cases, an iterative approach makes more sense: design something, build it, test it, learn from it, and refine the requirements as you go.

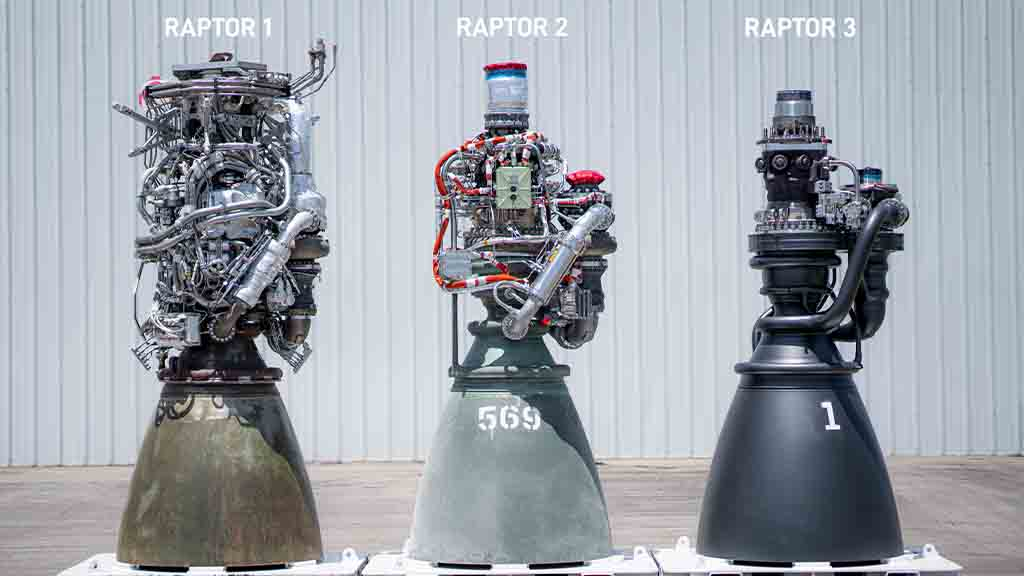

SpaceX’s Raptor engines are a good example.

The Raptor 1 engine did the job, but as seen above, was a lot more complex, as the team spent time figuring out how to achieve the requirements the first time. This meant the system was complex and difficult not only in operation but maintenance as well. It's final engine mass was 2080kg, but this came with a Christmas tree of external tubing, meaning more potential leak/failure points.

With the lessons learned from the first iteration, the Raptor 2 was able to be designed and built much lighter, weighing in at 1630kg. Still a complex system, naturally, for a rocket engine - but more streamlined, removing redundant components like torch igniters (which ignite the propellant) and reducing the external plumbing.

By the time the Raptor 3 was developed, the process had been refined further. Using additive manufacturing, what was previously a set of externally fed channels could be now embedded into the engine to reduce weight and allow the system to be streamlined further. The final system weighed 1520kg, giving an almost 25% improvement in mass, and a higher specific impulse.

In the iterative process, requirements evolve alongside the system itself, allowing for gradual development of continuously better products.

Incremental Life Cycles

Here, functionality is delivered in stages.

Think of Google - starting out as a basic search engine, an initial version of the system was released early, then add features over time. Each increment provided value, while allowing learning and feedback to shape future development.

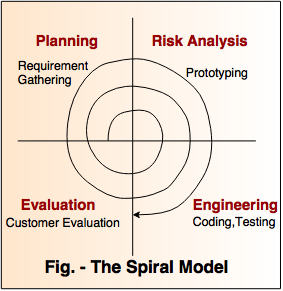

Spiral Life Cycles

For high-risk or uncertain projects, spiral models focus on repeated cycles of risk identification, mitigation, and review.

Each loop around the spiral reduces uncertainty, with heavy stakeholder involvement and frequent reassessment.

This approach is common in digital systems and data-heavy projects.

And in reality? Most large projects combine elements of several models.

Why Life Cycle Management Matters in Systems Engineering

So we've defined that all of these are possible life cycles, ways of taking projects from start to finish, and defining what needs doing when. But is that upside really worth the time spent on it?

In the vast majority of industry projects - the answer is a definite yes. By defining stages and expectations early, life cycle models help engineers:

- Make better decisions by understanding where the project is at different points in time

- Align disciplines, so different teams know what level of detail or assurance is required at each stage

- Reduce risk by introducing reviews, stage gates, and early verification activities - allowing teams to stay on task

- Improve traceability — tracking requirements, changes, and performance across time, so goals aren't lost

- Plan testing and validation activities in a structured, intentional way

Life cycle management encourages engineers to ask:

- Where is this system going to end up?

- Who will operate it, maintain it, or rely on it long after we’ve moved on?

- What decisions today are we quietly locking into the future?

In systems engineering, we often sit at the boundaries between design, operations, and safety. Life cycle thinking gives us a framework to connect those boundaries across time — not just across disciplines - which makes projects easier to accomplish overall, for everyone involved.

If you've read something on here and loved it, or want to read more, feel free to shoot me a message on my socials:

Instagram:

LinkedIn:

The feedback helps massively. Thanks!