What is Systems Engineering?

“I’m a systems engineer.”

“…What does that mean?

What kind of systems?

So...what exactly do you do?”

These are all questions I find myself answering a lot more since I started my new job 6 months ago. If you’d asked me a few years back what systems engineering meant, I probably would’ve said something vague like: “It’s the discipline that makes sure everything works together.”

And the truth is, “systems engineering” as a term still feels somewhat abstract to me today - which is why when I introduce myself nowadays, I add on ‘rail’ or ‘safety critical’ to give people a better idea of what my work actually involves.

Since I've started work as a System Safety engineer at Mott MacDonald, I’ve realised that systems engineering is less about one single technology or project, and more about the connections between technologies, teams, and decisions.

I've learned to understand that as a discipline, it's arguably one of the most challenging in engineering to understand and explain - not just because of its technical complexity, but the fact that unlike more design-focused roles, it requires a more abstract, high-level understanding of engineering operations in a project. And those operations will shift from sector to sector, project to project, and even throughout the course of a project.

So with this, my first post as I return to blogging, I thought it would be great to do a deep dive on what I've learned in my first 6 months, working as a systems engineer.

🧩 What Is a System?

Let’s start simple.

A system is just a collection of parts that work together to achieve a purpose.

That could be:

- Your phone, where hardware, software, and the user interface form a tightly coupled system, to allow the user to do things like scroll LinkedIn or read a blog post (persay).

- A train station, with tracks, power supply, signalling, passengers, and operators all interacting.

- Or a spacecraft, where every subsystem (propulsion, thermal control, communications) must operate seamlessly in a harsh, unforgiving environment.

What makes systems fascinating is that the interactions between parts often matter more than the parts themselves. A perfectly designed component can fail if its neighbour behaves unexpectedly.

In rail, that might look like a signalling subsystem working perfectly in isolation, but interacting poorly with a new train control algorithm. In space, it might be thermal feedback causing interference with communications.

The problems are different — but the thinking is the same.

🧠 How Systems Engineers Think Differently

Most engineers are trained to think within systems — to understand the details of specific designs, so that their aspect of a project (mechanical, electrical, civil etc.) can work perfectly.

Systems engineers, on the other hand, think between these systems.

They ask questions like:

- “What happens when this subsystem interfaces with another?”

- “Who is responsible for this function, and when it goes wrong? (note: something will always go wrong, so it has to be designed for)”

- “What are the assumptions we’ve made with this system that could cause failure later when the parts combine to make a whole?”

Looking at it from this perspective, an engineering project becomes a complex web of disciplinary threads, each one requiring the proper management to keep the web together.

Where a mechanical engineer might design a perfect bracket, a systems engineer worries about whether that bracket is strong enough, maintainable, documented, and understood by everyone downstream who it will be relevant for - including the electrical engineer who might start channelling wires through it (for example).

Systems teams act as translators between disciplines — helping engineers from different disciplines (electrical, civil, mechanical, software) speak the same technical language, so that challenges can be foreseen and addressed, and progress can be can be communicated onwards.

🧩 Design vs Integration

Another big shift in mindset came for me when I realised that systems work involves much more integration than design. What does that mean?

- Design is about creating a subsystem that works.

- Integration is about ensuring all subsystems can work together.

And for this reason, a lot of systems engineers will spend time understanding engineering designs rather than working directly on them. Systems is often about foreseeing challenges, and solving them on behalf the engineers who might not spot those potential issues early on.

This is what originally made me fall in love with the discipline from my university projects. In 2024, as I took up the role of project lead in my drone team, which had grown from 10 to over 50 engineers over three years, working on a UAV for remote medical supply delivery - I realised something important:

Whilst myself and the other students in our team from different courses (aeromechanical, avionics, computer science and automatic control systems) were spending time learning about and improving their individual subsystems, delays almost always stemmed from poor communication about how those subsystems would integrate.

My role slowly shifted from obsessing over technical details (though verification was still vital) to guiding teams in the right direction - identifying the barriers that could derail us if ignored.

- Would our battery and connectors work with the power distribution board we'd bought?

- Had we documented the number of ports needed from the flight controller to all our peripherals?

- Would our fuselage design meet minimum flight performance requirements, after all the avionics was installed?

Answering these questions was my first step into systems engineering — understanding interfaces, requirements, and the methods for verification and validation (more on this later).

Now, having moved to the industry - the language I use has started to change as well. Interoperability and compatibility are terms you’ll hear very often in the rail industry. On major rail projects, you can see this play out daily. You might have dozens of design packages — from tunnel ventilation to signalling control — each developed by different teams, often in different organisations.

Individually, they’re brilliant. But when integrated into one network, even a small assumption mismatch (say, about voltage tolerances or operating modes) can cascade into major system-level risks, unless those risks are identified before construction, and mitigated - which has made up a lot of my work in these last 6 months!

That’s why we run HAZID workshops — sessions where we bring together designers, contractors, operators, and safety specialists to pre-emptively identify hazards before they manifest in the real world.

It’s a perfect example of systems thinking in action: diverse perspectives collaborating to make the system safer, not just finish the design.

🧭 Functional vs Physical Architecture

This idea confused me for years, but the last 6 months have helped me understand it and it's importance - so let’s simplify it.

- Functional architecture = What the system does. (e.g. detect a train, send a signal, open a door)

- Physical architecture = How it’s built. (e.g. sensors, cables, relays, software modules)

On major projects, regardless of the industry - from rail to space - engineers build complex systems like signalling or power distribution, by first defining their functions — what needs to happen, in what sequence, and under what conditions.

Only after we understand those functions clearly do we decide how to implement them physically.

For example, when planning a spacecraft mission: you first define the mission functions (“communicate with Earth,” “maintain orbit,” “power subsystems”) before deciding whether to use solar panels or RTGs.

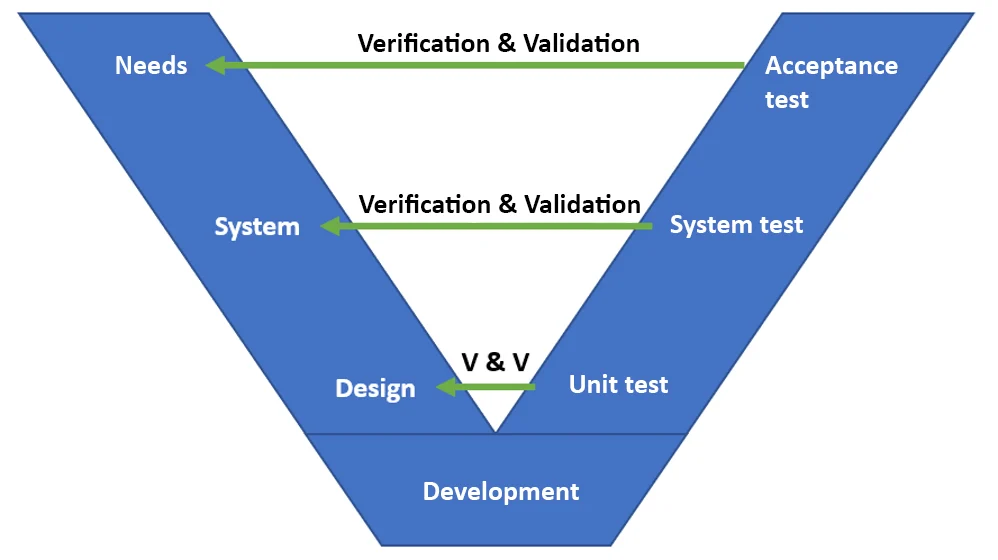

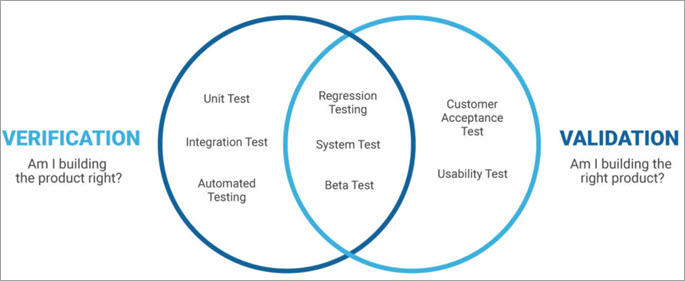

✅ Verification vs Validation (V&V)

These two terms are everywhere in systems work, but they’re often misunderstood.

- Verification asks: “Did we build the system right?” (i.e. does it meet the design requirements?)

- Validation asks: “Did we build the right system?” (i.e. does it meet the real need?)

In rail, verification might mean checking that a braking system activates within the specified time.

Validation would be making sure that the braking system actually makes the network safer for passengers.

In aerospace, same logic — a spacecraft might pass every verification test but still fail its mission because it didn’t meet the user’s operational needs.

That distinction is key to understanding systems thinking — and why systems engineers sit at the intersection of design, safety, and operations.

💡 The 7 Golden Questions of Systems Thinking

Over my time working as a systems engineer, I’ve developed a framework - a mental checklist that I like to come back to every so often, for project meetings, design reviews, or safety workshops:

- What is the system trying to achieve?

- What are its boundaries?

- What assumptions are we making?

- How do components interact?

- What could go wrong — and how would we know?

- Who’s responsible for each outcome?

- How do we know the system really meets its purpose?

I’ve found that if you can answer those seven questions clearly, you’re already practising systems engineering — even if your job title doesn’t say it.

And with that, here's what a quick internet search of systems engineering shows:

Having read this post, hopefully these explanations make a bit more sense!

If you've read something on here and loved it, or want to read more, feel free to shoot me a message on my socials:

Instagram:

LinkedIn:

The feedback helps massively. Thanks!